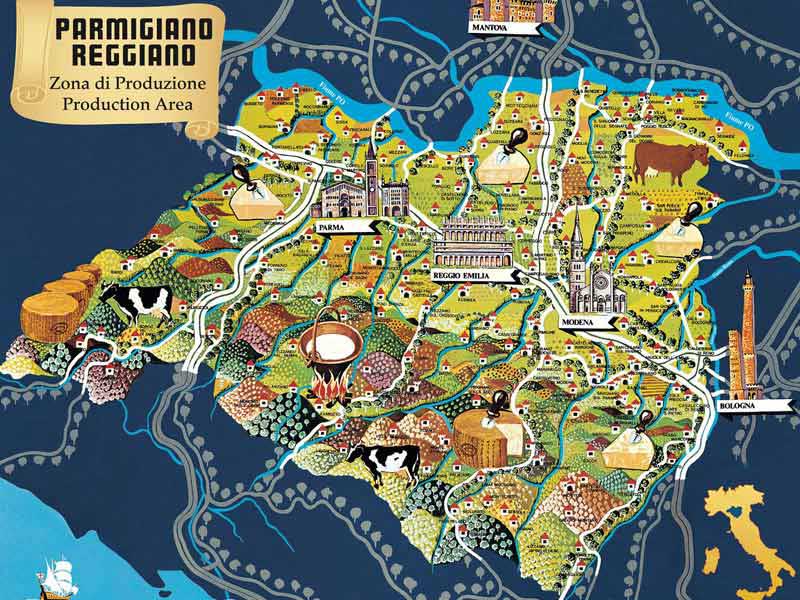

I recently went on a trip to Italy with my friends. The trip turned out to be wonderful: not lacking in adventure (a lot of funny things happened to us), and it also had some educational aspects (we learned a lot of interesting things there). For one, we learned how our favorite cheese is made. Italy, as I'm sure you know, is the birthplace of parmesan cheese. And real, classic parmesan — Parmiggiano–Reggiano — is produced only there, in a rather small region that includes the provinces of Parma, Reggio–Emilia, Modena and certain parts of Bologna and Mantua, between the rivers Po and Reno. The name "Parmesan" can be legally used for some cheeses produced according to the same recipe outside the region, but only the cheese produced within these boundaries can be proudly called with its full name: Parmiggiano–Reggiano. Parmiggiano stands for the Parma region and Reggiano for the Reggio Emilia region.

To find out the secrets of Parma cheese–makers, we had to work hard… Before heading to Parma, we contacted an expert on Italian food and cycling enthusiast Davide from BikeFoodStories.com, and planned a bike tour to a cheese factory with cheese tasting and a subsequent bike city tour with prosciutto tasting. After all, Parma is also known as the capital of Prosciutto! Davide takes this all very seriously. This is not surprising; food is a serious matter. Especially for somebody who graduated from university with a degree in gastronomical science. We met up with Davide in his office near the bicycle parking where his 13 bikes are docked. You can rent a bike and ride all by yourself if you already know where to go and what to try, but we decided to trust an expert, and fifteen minutes later our caravan could be seen on the streets of the city: three (hopefully) elegant ladies led by a handsome black-bearded man.

We left the city, swept past the headquarters of the pasta producers Barilla — this name, I think, is known to many lovers of Italian pasta — across fields and meadows along rural roads to one of Parma's many cheese factories.

They have already become accustomed to visiting tourists, so naturally there is a small cheese/gift shop in the same building. Here we will have a cheese tasting. But this will happen later; for now we are going to find out how our beloved parmesan is made. We put on plastic gowns, caps, and boot covers, and follow Davide to a large room. One of the first things to catch our sight is the row of huge, beautiful, shiny copper vats in which workers stir something with large wooden shovels (or oars, as they resembles both).

Upon closer inspection, you can see a huge round ball emerge from deep beneath the surface in each vat. Like a cheese moon! Here it is: soon-to-be-Parmesan. We arrived just in time to observe a fresh cheese ball divided into what will become a wheel we see in stores.

It takes two men to do the job. First, one worker turns the paddle in the vat to push the cheese ball closer to the surface. The second quickly places under the ball a piece of muslin cloth, tied to two long poles. The poles are placed on the edges of the vat so that the cheese head doesn't sink again. Once the whey has drained a little, the cheese ball is cut in half with a huge cleaver. Then one worker gently shakes the improvised stretcher and one half moves into the second piece of cloth, which his partner brings from below. Each such half weighs 50 kilograms.

Then the pair moves to the next vat. Can you believe how strong these cheese makers are? Honestly, if they were sent to the Olympics, they could easily lift the strongest weightlifter along with their barbell, I am sure! While the divided cheese heads hang over the vats, we go up to the top of the hall. There are huge shallow baths for the first stage of making Parmesan. As Davide explains to us, the owners of the cows are united in cooperatives, because the equipment for the production of cheese is very expensive and it is much more economical if several farms hand over milk to one cheese factory. Every morning and evening, a truck goes to the surrounding farms and collects fresh milk. The evening milk is poured into shallow baths and left overnight for natural separation to begin. The temperature in the room is not regulated, so winter cheese differs slightly from summer batches in taste and aroma. Although honestly, in order to find these differences, one must probably eat a lot of Parmesan! Evening milk is skimmed and then mixed with morning milk in certain proportions, the mixture is fermented, and all the liquid is poured into copper vats, where after about an hour the future cheese begin to form. While Davide tells us some very interesting facts about the whole process of parmesan making, we try to lift some cheese-making tools and tap and feel the cheese. Eventually, it is time to transfer the soft cheese heads to the molds. Fabulously strong men lift knots with fifty-kilogram heads and shift them into molds.

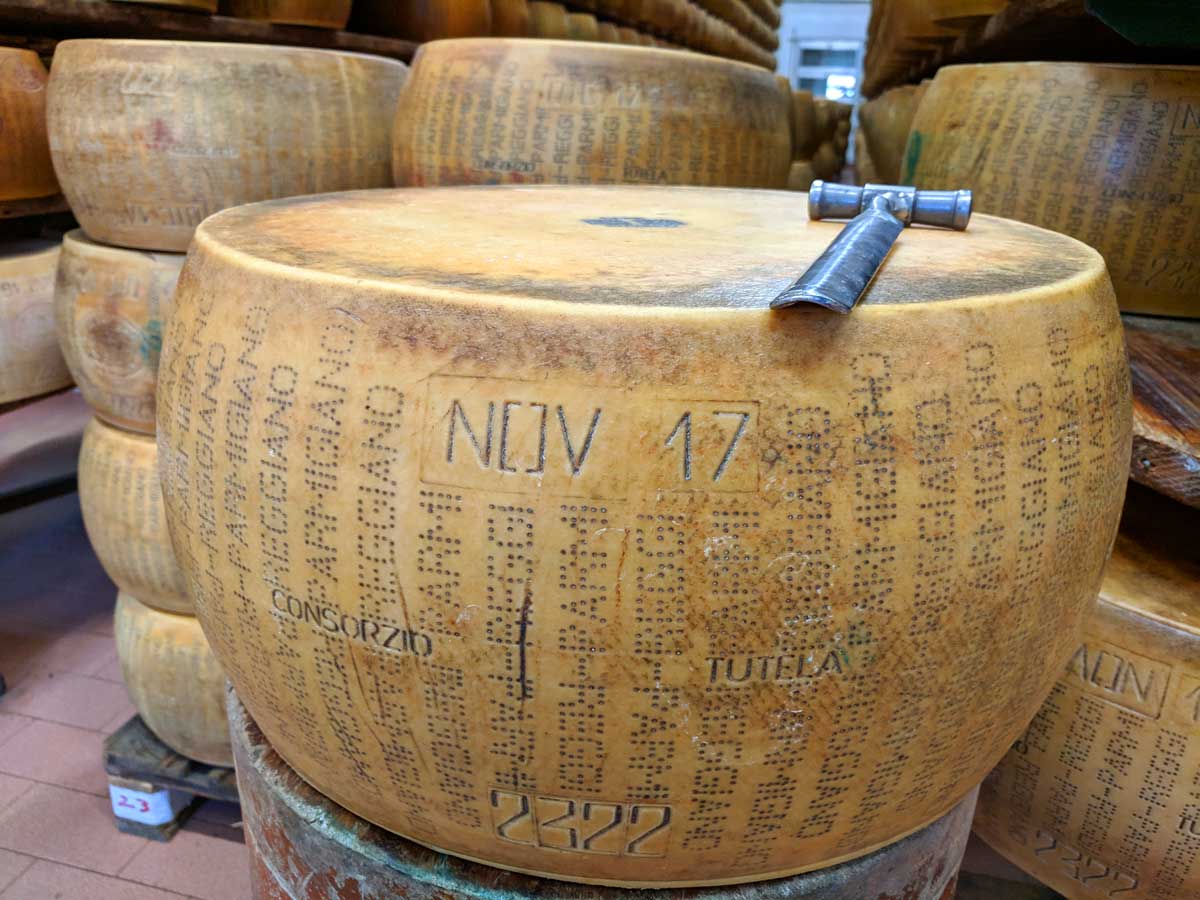

After a few days they are taken out and then placed into the stainless steel springform, now sporting a plastic belt with molded letters and numbers that will be imprinted into the cheese crust. It reads: "Parmiggiano-Reggiano" all over, and there is also the date of production along with the factory number. This is the famous Parmesan jacket!

The excess whey begins to run out and gradually the cheese balls begin to turn into the wheels that we see in stores. Later, these wheels are placed into salt baths in order to soak in some salt.

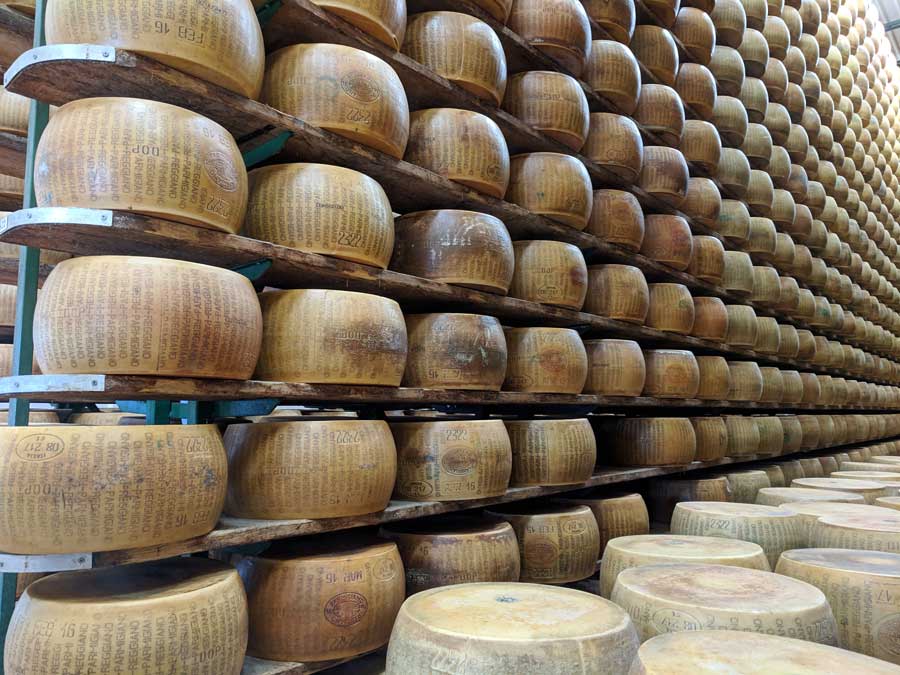

After another five days they are caught, dried, and sent to storage, where cheese ripens for anywhere from one to a whopping three years. Davide suggested that we look straight down when entering the "'Wow!' Room" and only then look up.

Wow! This is precisely the first word that visitors breathe out upon entering this huge hall packed with shelves where cheese wheels rest. This cheese vault is definitely impressive! I recall the cartoon "Tom and Jerry". Jerry would have decided for sure that he had gotten into mouse heaven! Davide told us in great detail about all the stages of making Parmesan and even played a cheese overture with a special hammer to determine the readiness of the cheese. This is exactly how experts determine whether Parmesan matures correctly: they tap a wheel with a special hammer and listen to whether the tone is the same all over and whether it sounds right.

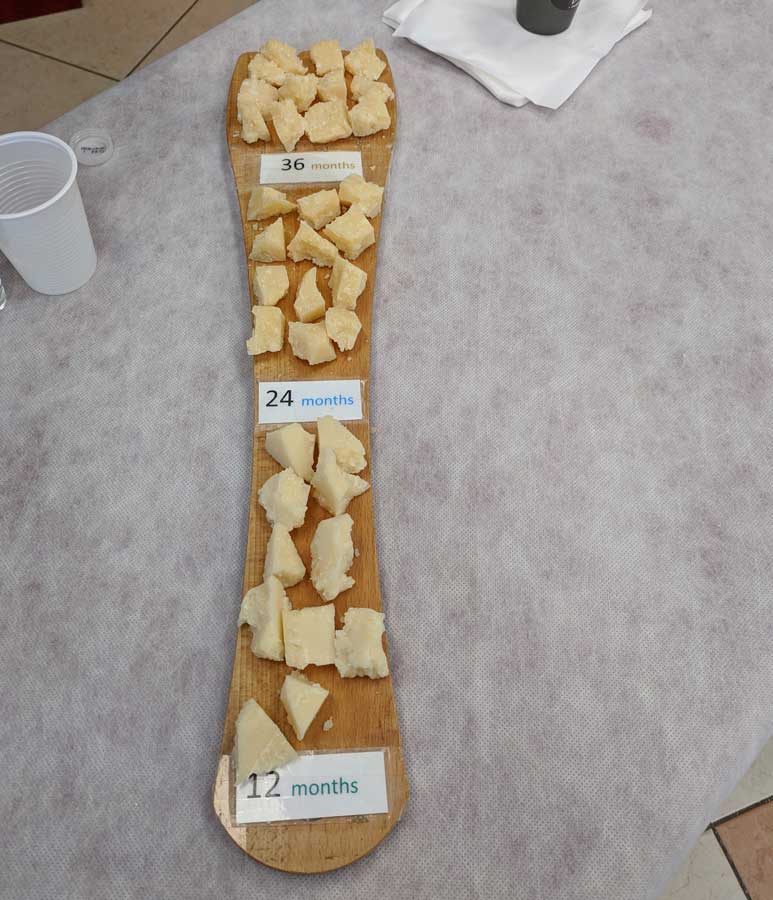

We also tried to play the role of experts, knocking and carefully listening. And yes, we were even able to hear the difference between the right cheese and the not quite right cheese! And finally, the time came for parmesan tasting! We tasted parmesan aged one, two and three years.

Indeed, there is a very noticeable difference in taste. It is not that any one of them is better or worse, they just have a different degree of richness of taste, different notes. The "young" one year old cheese is very delicate and somewhat creamy while the three-year-old has a more mature, rich, nutty, slightly sour taste with a nice crunchy texture. It is also interesting that Parmesan is often eaten not with bread or crackers, but just on its own, or with a drop or two of aged balsamic vinegar of Modena. Try it this way, you will definitely enjoy it! Why not throw a parmesan tasting party? After all, if you eat cheese with someone, you become good friends. I am happy to have a new friend in faraway Italy who generously shared with us his love for parmesan and biking.